Excerpted from: (Page, Frank, Lardner. Assessment and Treatment of Muscle Imbalance, The Janda Approach. 2010, Human Kinetics, Champagne IL.)

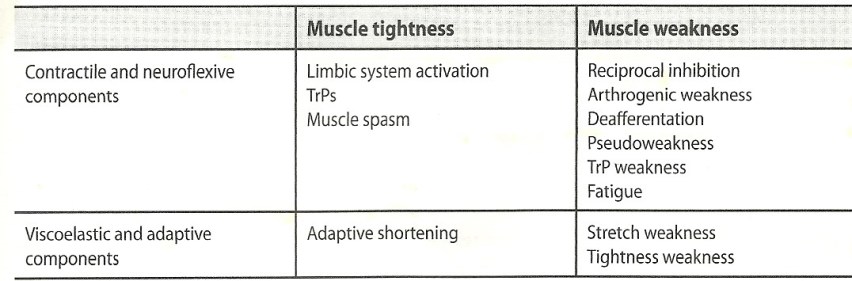

Janda found that the typical muscle response to joint dysfunction is similar to muscle patterns found in upper motor neuron lesions, concluding that muscle imbalances are controlled by the CNS. Janda believed that muscle tightness or spasticity is predominant. Often weakness from muscle imbalance results from reciprocal inhibition of the tight antagonist. The degree of tightness and weakness varies between individuals but the pattern rarely does. These patterns lead to postural changes and joint dysfunction and degeneration.

Janda identified three stereotypical patterns associated with distinct chronic pain syndromes: the upper crossed, lower crossed, and layer syndromes. These syndromes are characterized by specific patterns of muscle tightness and weakness that cross between the dorsal and ventral sided of the body.

Upper-crossed syndrome (UCS) is also known as proximal or shoulder girdle crossed syndrome.

The UCS pattern of imbalance creates joint dysfunction, particularly at the atlanto-occipital joint, C4-C5 segment, cervicothoracic joint, glenohumeral joint, and T4-T5 segment. These focal areas of stress within the spine correspond to transitional zones in which neighboring vertebrae change in morphology. Specific postural changes are seen in UCS, including forward head posture, increased cervical lordosis and thoracic kyphosis, elevated and protracted shoulders,and rotation or abduction and winging of the scapulae. These postural changes decrease glenohumeral stability as the glenoid fossa becomes more vertical due to serratus anterior weakness leading to abduction, rotation, and winging of the scapulae. This loss of stability requires the levator scapula and upper trapezius to increase activation to maintain glenohumeral centration.

Lower-crossed Syndrome (LCS) is also known as distal or pelvic crossed syndrome.

This pattern of imbalance creates joint dysfunction, particularly at the L4-L5 and L5-S1 segments, SI joint, and hip joint. Specific postural changes seen in LCS include anterior pelvic tilt, increased lumbar lordosis, lateral lumbar shift, lateral leg rotation, and knee hyperextension.

If the lordosis is deep and short, then imbalance is probably in the pelvic muscles; if the lordosis is shallow and extends into the thoracic area, then imbalance predominates in the trunk muscles

Janda identified two subtypes of LCS. Type A patients use more hip flexion and extension movement for mobility. Their standing posture demonstrates an anterior pelvic tilt with slight hip flexion and knee flexion. These individuals compensate with hyperlordosis limited to the lumbar spine and with a hyperkyphosis in the upper lumbar and thoracolumbar segments.

Jandas LCS Type B involves more movement of the low back and abdominal area. There is minimal lumbar lordosis that extends into the thoracolumbar segmants, kyphosis in the thoracic area, and head protraction. The COG is shifted backward with the shoulders behind the axis of the body, and the knees are in recurvatum.

Deep stabilizing muscles responsible for segmental spinal stability are inhibited and substituted for by activation of the superficial muscles. Tight hamstrings may be compensating for anterior pelvic tilt or an inhibited gluteus maximus.

LCS also affects dynamic movement patterns. If the hip loses its ability to extend in the terminal stance, there is a compensatory increase in anterior pelvic tilt and lumbar extension. This compensation creates a chain reaction to maintain equilibrium, in which the increased pelvic tilt and anterior lordosis increase the thoracic kyphosis and cervical lordosis.

In adults, muscle balance begins distally in the pelvis and continues proximally to the shoulder and neck area. In children, this progression is reversed, and muscle imbalance begins proximally and moves distally.

Janda’s Layer Syndrome (also referred to as stratification syndrome) is a combination of UCS and LCS.

Patients display marked impairment of motor regulation that has increased over time and have a poorer prognosis than those with isolated UCS or LCS due to the long-standing dysfinction. Layer syndrome is often seen in older adults and in patients who underwent unsuccessful surgery for herniated nuclus pulposus.

While chronic pain is difficult to treat, clinicians must be able to recognize Janda’s UCS, LCS, or Layer Syndrome in order to provide appropriate treatment.